Available now at your local comic shop, Barnes and Noble, or online via Amazon - Marvel's Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. Season Four Declassified! Dive into the world of Ghost Rider, LMDs, and the mysterious and backwards Framework is this must-own collectable hardcover. Within the pages, get episode synopses, analysis from the cast, creators and writers of the show, behind the scenes tidbits and documentation, photos, artwork, and a whole lot more! As always, this book was an absolute joy to write from start to finish. For more information head to the book specific page here on the site!

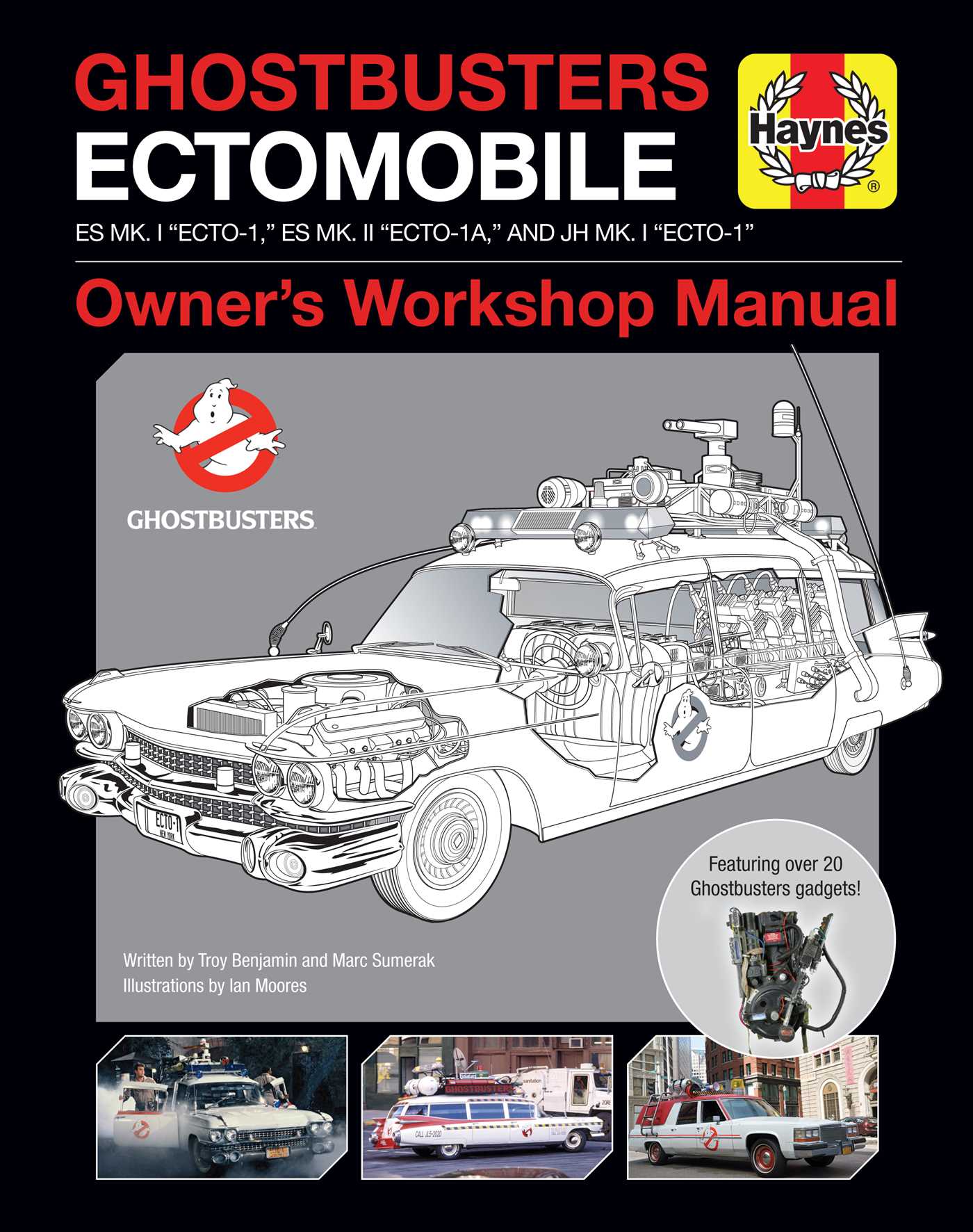

Coming in October: The Ghostbusters Ectomobile Owner's Workshop Manual and Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. Season Four Declassified

It's a busy October for Troy Benjamin-penned book releases! Coming up in a little more than a month, Ghostbusters and Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. fans can look forward to two new exhaustive volumes to read on those crisp fall evenings with the Ghostbusters Ectomobile Owner's Workshop Manual and Marvel's Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. Season Four Declassified.

Ghostbusters Ectomobile

Owner's Workshop Manual

Go under the hood of the Ghostbusters’ iconic car and discover the secrets of the team’s ghoul-trapping gadgets with this comprehensive users manual for Ecto-1 and the equipment it carries.

Discover the secrets of the Ghostbusters’ iconic specter-smashing automobile, Ecto-1, with this comprehensive owner’s workshop manual. Along with a detailed breakdown of Ecto-1’s capabilities and exclusive cutaway images that show the car’s souped-up engine and onboard ghost-tracking equipment, the book also focuses on the Ghostbusters’ portable tools of the trade, including proton packs, ghost traps, and PKE meters. The book also looks at various models of Ecto-1, including the Ecto-1A from Ghostbusters II and the version of Ecto-1 seen in 2016’s Ghostbusters: Answer the Call. Featuring commentary from familiar characters, including Ray Stantz, Peter Venkman, and Jillian Holtzmann, Ghostbusters: Ectomobile: Owner’s Workshop Manual is the ultimate guide to the Ghostbusters’ legendary vehicles and the ghost-catching equipment the cars haul from one job to the next.

Marvel's Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.

Season Four Declassified

New top-secret details on Marvel's Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. Season Four await in this keepsake volume! While ex-agent Daisy Johnson tracks down threats to her fellow Inhumans, former S.H.I.E.L.D. Director Phil Coulson is tracking her - and new player Ghost Rider is hot on both their trails. And the intrigue only heats up: With Life Model Decoys infiltrating S.H.I.E.L.D.'s ranks, who can Coulson trust? The world of S.H.I.E.L.D. continues to evolve, hurtling toward an astonishing Season Four conclusion that will leave our team's lives barely recognizable. This incredible new volume showcases never-before-seen photography, production-design details and exclusive behind-the-scenes information and interviews with cast and crew. The events of Marvel's Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.'s fourth season will rock the characters you know and love to their core. Don't miss a single detail!

The Godfather of Modern Films Wants to Save The Industry - Part Three

Note: The following is a first-hand account of my experience meeting film pioneer Douglas Trumbull in early 2015. This story and interview has been posted with his permission. This is part three of a three part series.

Presented here is the remainder of the transcript of my conversation with Douglas Trumbull. In yesterday's post, we discussed the evolution of space and space travel in films over the decades. Now, conversation turns to the future.

In the more recent era of theatrical experiences, you’ve got the 70mm and IMAX experiences, what are those doing for space films and helping bring the audience and so they kind of forget they're sitting in that seat?

TRUMBULL: That's what we are doing here [at my studio] right now, is trying to figure out how to go beyond the limitations of film. And I've been probably one of the strongest advocates of large-format IMAX, Showscan, 70mm, Super Panavision, you name it, I'm for it and have been all my life. And all the movies that I've done that have had the, you know, hung around for a long time have had the effects at least shot in 70mm, 65mm negative. And I'm very proud of that because it's high-quality.

One of the problems that's besieged the digital industry is that it started out that television was digital, right? And so people started adapting television cameras and trying to make movies with them. And the quality was just never good enough. And so it kept getting better and better and better and Sony and Panasonic and other companies came up with digital cameras that have more resolution… And then they tried to approach film.

But the truth of the matter was, over the last 20 or 30 years, digital had this reputation for never being as good as film. It could never quite get there. Film just had this texture and this clarity and this vividness that was just unsurpassed. And that's one of the aspects of people’s habit about what they expect. When I started looking into the issue of digital frame rates and resolution and screen size and brightness and all kinds of issues that I think need dramatic improvement to make movies better, I realized that digital enabled all that to happen and film did not.

So I started shooting tests at 4K instead of 2K, which is four times the image resolution. And at 120 frames a second instead of 24, which is five times the frame rate. So there's much less blurring, everything is sharper projecting on much bigger screens, much more brightly because 3-D movies you see in movie theaters these days, there are three, four, five stops lost and it’s pathetically dim and very hard to watch. It creates a tremendous amount of eyestrain.

I thought if we get brightness back up and try to do the stereo space more comfortably where the field of view of the camera matches the field of view of the projection, it's very important to reconstruct a normal sense of perspective, suddenly your eyes can relax. They say, "Oh, that looks natural to me." I'm focusing more on converging, all my muscles are not, you know, going into agony trying to converge on an actor who is three feet away, but the screen is really 60 feet away. That creates eyestrain.

So I started trying to solve all these problems. And I discovered this territory and we call it Magi, which is this process we are working with, which is a way to use digital technology to solve all the old problems of film and do something that is actually substantially superior in every way so that we are not limited by film frame rates, we’re not limited by film grain, we are not film, limited by shutter closing or any of those things. And it's opening up this whole new territory that I'm really excited about as a filmmaker. I've done it because it's my next widget. I want to make films with it, I'm not just an engineer in the lab trying to solve a technical problem, I want to make movies that are totally immersive and hopefully almost indistinguishable from reality.

When you're sitting in your seat and you're looking at this gigantic screen that's wider than Cinerama ever was or wider than IMAX ever was and brighter and clearer and sharper and more 3-D depth, it brings up a whole new sense of immersion like being there. And so we are at this moment in time where I just finished this little film called UFOTOG and we’re starting to show it to the industry and see if directors and studios say oh wow, we could actually get people back into theaters because this is, you can’t get this on your tablet, you can’t get this on your television set, you can’t get it on other media, you've got to go to a theater to have this experience. And we will see if it gets some traction.

That's what gets people back in the theater, because they want that experience they can't get at home.

TRUMBULL: Yeah, and the movie, the movie business is in kind of a crisis right now. I mean theaters are closing. Exhibitors who run multiplexes don't have enough product to show. Studios are not making enough movies. And studios find themselves trapped in the syndrome of the blockbuster, tentpole franchise, repeatable syndrome of giant scale, special-effects driven movies that are exportable. They don't export American social values, they just export comic heroes or whatever, which plays in foreign. Because 75% of the money is coming from foreign markets. The DVD sell-through has plummeted. So it's a completely new business model for the movie industry and young people today are finding that whoa, they can stream, download, get Netflix, YouTube, you name it, they can get the story on tablet for a fraction of the cost of going to a movie theater and it is creating a crisis.

So my agenda is to solve that problem. So if you go to a movie theater, you're going to get something that is truly spectacular and truly immersive and transportative and emotive and all the other stuff the movies have to be. It's not like special-effects or high frame rates are going to replace the drama that a movie has to have. It's got to be everything. And if we can get there, I think we can, we can revive the movie industry. I think we really can, I think it's well within reach right now. It's very easy to do, it's elegantly simple, it's not very expensive, and it means we’ve got to just rethink the whole thing.

When a young mind that goes to the theaters and sees a movie like Gravity, what is the widget or innovation that they are going to come up with 15 or 20 years down the line inspired by what they've seen?

TRUMBULL: I don't know. I subscribe to the GoPro movie of the week. I mean if you follow GoPro, it's a camera that you can bolt it to your head, you can bolt it to your wrist, you can put it on your feet, you can put it on your surfboard, you can put it on your skis, you can put it on your motorcycle and make these incredibly immersive experiential movies with a camera that costs 200 bucks that can go anywhere that is indestructible and will run for two hours uninterrupted, you don't need to edit or cut or turn it on or off or anything. It's enabled, it's a whole new kind of super immersive high-intensity sports kind of activity to be filmed, but it's only being shown on a tablet or your computer.

It's not quite good enough quality to put on a big screen. And I'm thinking, what if we could make tiny cameras that could do this Magi process like a GoPro camera but it's going to look like this, and kind of crowd source content. Take these cameras, go make whatever you want. You want to do special-effects, greenscreen, it's ubiquitous, easy, you can buy it at, you know, Best Buy and you're in business, you know, you got your laptop, you've got your camera, you got your little editing program, you're in business.

So I think it's a complete paradigm shift in what content can be. It's not that we won't want to make very complex expensive special effects epic extravaganzas, they're great and it's the only way to get there, you know, you can't GoPro your way into The Avengers or something. But there's plenty of room for everything. I think people seek alternative experiences, they seek out of body experiences. We feel limited by the physicality of our senses, what we can hear and what we can see and what we can feel.

And so when you go to a movie theater you want to be taken away, you want to go to space, you want to go underwater, you want to go to Mount Everest, you want to go to another dimension in time, or whatever. Get me out of here, because I have all, I have my everyday life every day, you know, so, movies have always provided that kind of alternate reality.

You can be immersed with characters or you can get immersed with this crazy guy who has put a GoPro on his head to skydive...

TRUMBULL: And the thing that I try to get a grip on is that media, like movies or television tells stories, okay? So if you are going to aim a camera at an actor or actress and you are going to tell a love story or a crime story or a whatever story, it's a story. It has a beginning, middle and an end, it’s dialogue, it’s conflict, it's all kind of stuff that is literature. And the thing that I was profoundly affected by when I had the good luck to work with Stanley Kubrick on 2001, he said, I'm so tired of melodramatic cinema conventions and over the shoulder shots and two shots and master shots and close-ups.

He was completely bored with this. He wanted to make this immersive movie, and he knew he had this palette, these 90’ Cinerama screens around the world, it was called Cinerama at the time, 90 foot deeply curved screens. And he felt that this was an opportunity to change cinematic language and make the audience feel like they were going to be on this adventure in space. And so when it came to shooting a scene like the Stargate sequence, and Keir Dullea is in the pod, any director would cut to a reverse angle on Keir and they would cut to an over the shoulder shot of Keir, over the shoulder looking out the window of the pod, all the normal cinematic language stuff would be there.

Kubrick started doing that and he said, I hate this. And he started dropping all those shots. Then he stopped even shooting shots like that. We did tests to try it and he said no, I want the audience to be in the pod going through the thing and get rid of normal cinematic convention and let the audience be there. Don't interrupt it with melodrama. So that became his direction for the entire style of 2001, was for him to get out of the way and let the audience go on this adventure. And that's the thing that sets 2001 apart from almost all other movies.

So when you're seeing him enter the Stargate, it's not a dirty shot with his shoulder in the frame? It's his point of view?

TRUMBULL: No, you don’t need it, you don’t need it. And you don't need to explain it. Did anybody in 2001 say on, "Hold on, we’re going to go through a Stargate,' or "we’re going to transcend time and space?" No one mentions anything, it just happens. And that is so cool. I mean, it completely distorted my career because I thought well, if this is what movies are like coming in, and then I found out it wasn't like that. After 2001 these giant Cinerama theaters were chopped up into multiplexes and the big pallet went away. The bit screens went away, everything went mobile, production went into trucks and went out on location and shot in the desert or in wherever, and the studios got rid of their backlots, they got rid of half their stages and the movie business went through this transition of trying to cut costs and make reality. Well, it's okay up to a point. But reality is not what I'm interested in.

It stopped being fun to you.

TRUMBULL: Yeah. In a way, cinemas kind of lost their way. And I think there is a tremendous history of experience and knowledge and technology that has been the underpinning of the movie industry from its inception. It's always been dependent upon what's the next lens, what's the next camera, what's the next projector, you know, what's the next recording device, what's the next multichannel sound system? You can’t ignore that, you have to say well, yeah, what is the next thing, how do we use it creatively to make a movie that provides something that is not just a story. Because if you want just a story, watch television. It's fine. Stories pass through television effortlessly. But if you want to make an experience, it's kind of a story, but it's something else.

Other filmmakers that you feel are using the techniques to good effect. So who are some of the filmmakers that you feel take technology and don't use it as the spectacle and make it the actual experience that brings audiences into theaters?

TRUMBULL: Well I think that there is a kind of a creative process that directors use. Christopher Nolan is a good example, Alfonso Cuarón is a good example, there's a few to them, JJ Abrams even. Many directors, they look at the available tools and they say oh, we could actually shoot this sequence, we could shoot a sequence with the set completely upside down and actors hanging on wires and we could make it look weightless or make it look like a dream or something like Inception and do this amazing thing, therefore what story am I going to tell because it would be cool to do that.

There's kind of an inverted creative process I think that goes on to say okay, now that Apollo 13 successfully actually shot real weightlessness in the vomit comet, wow that really looks real. And it was incredibly difficult to do and incredibly expensive to do, but the audience loved it. And so it was the availability of that plane to be able to do zero gravity that probably enabled the idea that oh yeah, we could do Apollo 13, you know what I'm saying?

It's the technology enabling a story. They are, they are woven together inextricably in creating an ability to do something that you couldn't do before. Because audiences are going to come to theaters because they want to see something that they didn't see the one. They don't want to see another Western, they don't want to see another crime thriller, leave that for television. They want an experience that goes beyond the limitations of television reality, you've gotta come up with a better mousetrap. And so it’s usually technological. And the thing that I'm trying to offer the industry right now is to say, well let’s break all the rules, use this digital technology and really push it to an extreme because we can do higher frame rates, we can do more resolution, projectors can project, screens can be bigger, it's not rocket science. There’s nothing we are doing here that isn't actually off-the-shelf.

And it's very cheap. It's all about data. And if you can get a terabyte of storage at Staples for $35, you have no data problems.

I'm just trying to nudge people out of the old world and get them to embrace something new and different.

Sounds like that's what gets you excited about it?

TRUMBULL: It is. I don’t do it because I’m a geek, I do it because I'm a filmmaker that wants to create an experience that I never saw before, that you never saw before. And that will be fun. So I developed the technology first to say okay, now what do we do with it? And like this little film here, we did a little test, a close-up of a friend of ours. He's not an actor at all, but I said but I want you to be two feet from the camera. I want you to look at the audience and I want you to talk to everybody that’s in that camera, the audience. Look directly at the camera, it's forbidden, it’s fourth wall, you don't do that in this process and I want you to pour your heart out, tell me your most intimate story.

And he did it and we were shocked and it enabled this whole development of something that I call first person experiential cinema to where it's like a hologram in the sense that it is completely, it seems completely real and the actor is talking to you. And the story is constructed, the story that we show here today is constructed so that it embraces the presence of the audience. It acknowledges your presence in the theater is important to that guy. He wants you to see what he is going to show, it's a secret, the CIA is after him, they're going to shut him down in an hour, he’s got, the clock is ticking. And by the time the movie is over, the fact that you saw the movie is his redemption. And that's a completely different dramatic construct than we've seen in movies.

But it's enabled by the technology, which is that that guy looks like he is right in your face talking to you directly, eye line contact. And when that is a big-name actor or actress or a really wonderful Shakespearean British, you know, Ian McClellan or something, he is looking at you as though you are the dwarf or whatever, I think it's going to be a paradigm shifter. And that's fascinating to me. It's like, it's like finding a new concept, it's like we don't have to adhere to these old rules, we can do something completely unknown and different.

Recently I worked with Terry Malik on Tree Of Life and that was a wonderful experience because Terry was looking for, he calls it the dao. He says, "I'm going to hope and pray that the camera is actually rolling when something unexpected happens." And so if you ever, if you know anything about how Terry Malick directs and constructs movies, he has a screenplay, or he has an idea and he gets his crew and his actors together. But while the camera is rolling and the performance is happening, he's talking constantly. They have to loop him out of the shot.

He is saying, “no, try this,” or, and he constantly gives them change-ups to try to get them to do something spontaneous that's unscripted and dynamically emotive in some way. And that transposed over to the visual effects for The Tree Of Life. We would go in on weekends to this really old building, it was just like a warehouse, and we would bring every conceivable kind of dye and road flare and burning stuff and tanks of liquid and shoot experimental stuff and see what happened.

That is so unusual in our industry - to do R&D with a crew on weekends and try to discover something that no one has ever seen before. And then combine that with computer graphics, we were using new compositors and stuff and the compositor was there with us. And he would say, well if you did this, I could take that and put it on that and then we could make an asteroid hitting the Earth and it’s going to look really great. So we would do that.

And it's that kind of fluid experiment, experimental openness that's unique, not unique to Terry, but unusual that I really admire. And it's the ability. Like Alfonso, I mean who would've thought you could use a big industrial robot to photograph an actress or actor and put their face into an animated character and make it look like that. I mean it's absolutely stunning and mind-boggling. I'm sure it didn't happen overnight. And it was probably a developmental process to figure out how to do it.

And then the whole thing that Jim Cameron did with Avatar of deconstructing the whole directorial process and motion capturing actors and actresses and then animating them to actually replicating their emotional persona as a blue Avatarian, it was mind-boggling. And then he could move the camera anywhere he wants in post-production and really stage incredible dynamic impossible-to-do camera moves and put that all together into a digital composite that just looks mind-boggling and it’s 3-D. So I say that's where I think the future of cinema is, if it's going to be this kind of experiential explore, exploratory. There is risk, you've got to have a new widget, you’ve got to go into a new territory. You almost have to invent a new thing on every movie.

Otherwise it gets old. I mean you can do Transformers over and over and over. You can do Spider-Man over and over and over until the audience will finally say, okay, enough already. Give me the next thing. But I just think we are in a really exciting time that's constrained by old habits. The old habits of 24 frames on a rectangular screen at the end of a box is boring. You've got that at home. And I think about it, the way like to express it, is I say okay, I’m sitting here and watching, I'm watching my tablet, okay? I hold my tablet, it's about that wide, so that's about 25° wide. If I look at my 80” flatscreen plasma TV that's 10 feet away from me, it's still about 25° and it's really almost no different, it's just a little farther away but bigger, it's no different.

You go to a theater and the screen is 40 feet wide, but it's 60 feet away, it's no different. If we want to really change the audience’s relationship and, and involvement in the movie, you've got to get that screen bigger. That's what they do in flight simulators. The rule in a flight simulator, if you want to convince a fighter jockey that he is in a cockpit, it better be over 100° wide. And if you talk to people like we work with people at Christie Digital in their flight simulation digital and say what frame rate you want this, they say we want 120 or 240 or 480. The more the better. It just gets more and more real.

If you want people to be immersed in their situation, that's what you do: Wider, bigger, brighter, faster. It just gets better. We could do that with movies now.

I feel like I'm a total lone wolf trying to do this. And I need some help and I need to be embraced by the industry and so we're going to start showing this and saying okay, let's come on. Let's join forces and do this because it's very easy to do.

And that, mixed with the collaborative process that people are challenged, it feels a good thing…

TRUMBULL: I mean you have to, you know, there's, historically there's a lot of people who, because of their insecurity, try to make their little widget secret. Big mistake, don’t make your widget secret. Give your widget away, be completely transparent. You've got to just throw it out there and say hey, you want to use it, you use it, do whatever you want. I will help you. But I'm not trying to tell you what to do with it, I'm just saying here is the widget and that could be in any form. But the kind of transparency that has, I think been borne out of the Internet and kind of a new way of working and doing business.

And it's troublesome because so many people expect to get something for free. And you can’t invent these things for free. There's got to be some payoff, there's got to be some way to make money, but it's probably a new business model too that you’ve got to, you've got to discover. We are in a scary time and an exciting time.

The interview comes to a close and I turn to my DP, Michael. The two of us share a look as if to say without vocalizing, "Wow, that really just happened?" I thank Doug for his time and for the incredible conversation. Which was far more than we needed for the brief 42-minute documentary. He asks if we'd like to join him for lunch before hitting the road. Of course, without hesitation, we all say yes.

We quickly wrap all of our gear and follow him back to the main house where an impressive spread of sandwiches, salads, cookies and more have all been laid out not just for us, but for all of Trumbull's crew. Lunches are shared fireside among the crew working for Trumbull in the cozy home, and we are among the few that are lucky enough to join in the ritual. Camera crew, construction, farmhands, assistants, everyone eats together as a family of about a dozen by my count.

I sit next to a table next to Doug and his wife Julia, who continue to be the most gracious of hosts. Everyone shares a comfortable silence, eating a hearty and delicious meal after a long day's worth of work. Suddenly the thought occurs to me that I'm sitting with the man behind Back to the Future: The Ride and it just happens to be the calendar year 2015. I can't resist and I tell him what a fan of the ride I am. I tell him how disappointed that I was Universal Studios decided to replace it with a fully-CG Simpsons attraction. He shakes his head and I worry that I've pushed too far, bringing up a sensitive subject. Instead, he takes a drink of his coffee and simply tells me that the film for the theme park ride was one of his proudest achievements. The making of the Back to the Future Ride film was incredibly complex. Bookending our conversation about having to invent widgets in order to get the job done, Trumbull had to help invent the technology not just to film the ride, but also to project it for the ride cars. He excuses himself from the table and walks to a shelf where he pulls out an album and sets it in front me. It's filled with photos and designs from the making of the ride. As I flip through the book, he points out people, equipment, elaborate and intricate miniatures, giving me the key details just as a proud grandfather would show off photos of his grandkids.

The sun weighed heavy on the horizon and despite wanting to stay and continue the conversation and enjoy the hospitality, the time had come when we all felt like we had outstayed our welcome... and were concerned we'd get lost trying to find our way out of the Berkshires in the dark. We said our goodbyes and before I knew it, I was back in my rental car and on the Turnpike.

This time, I avoided the EZPass mistake but was completely lost in thought for the multi-hour drive. No radio, no music, just a couple hours with myself reflecting on the experience as I drove back to Boston. Immediately upon checking into my hotel room, I dropped an email to Doug and Julia thanking them for their gracious hospitality and for being so welcoming.

My last contact with Doug was later in the spring of 2015, informing him that the company that I was working with was dissolving our group. I reiterated to him just how much my experience at his farm meant to me and asked if he'd be okay with me posting the article that you've just almost finished reading. The experience would be really hard to top and I wanted to find some way to document it for my own memory and to share with others.

Shortly after we were all let go from our employer, I made the decision to step away from DVD/Blu-ray behind the scenes work. Much like Trumbull speculated in our interview, the work was slowly starting to dry up as streaming and on demand services slowly began to wither the physical media formats. The "Looking to the Stars" documentary and the experiences and conversations that it brought me really felt like John Elway going out on a Super Bowl win. I called the project our own little tribute to my most prized issues of Cinefex Magazine - but incredibly, it was also my opportunity to talk face-to-face with all of the innovators and inventors that I'd read about in the pages of those magazines. Because of the documentary, I became acquaintances with John Dykstra as well. One of my proudest moments (and the last that I've done in the capacity of a EPK/DVD field producer) was on the set of X-Men Apocalypse, picking Dykstra's brain on how to effectively shoot a promo I was directing with Bryan Singer in slow-motion Quicksilver Time on the Phantom camera. At the end of our conversation, he asked what happened with the space film documentary we were working on. Luckily I happened to have a copy on me to give to him. It was such a strange moment, handing a hero of mine something that I had produced for him to watch.

Douglas Trumbull is one of the most talented and knowledgeable visionaries that not just the film medium, but technology as a whole has ever had in its corner as an advocate. Since day one of his career, he's pushed the envelope. He's been two steps ahead of everyone else. Frankly, looking back on the experience, I'm disappointed that the innovations that he's created while living the dream on his private estate in Massachusetts, still haven't been adopted and repopulated en masse in 2017. Imagine any of the films that you've watched and enjoyed the past couple years being in crystal clear, larger than life three-dimensions and just how much more it would have immersed you in the story. Imagine the dramatic and explosive conclusion to an epic like Game of Thrones not just on your 35" flatscreen TV in your living room, but surrounding you. Putting you right there in the thick of the battle. It's thrilling and exciting, it could be like the opening of Star Wars seeing the Star Destroyer fly overhead all over again. That's what Trumbull passionately wants for himself and for all of us.

And I still can't believe I got to spend nearly an entire day to share that excitement and enthusiasm with him.

The Godfather of Modern Films Wants to Save The Industry - Part Two

Note: The following is a first-hand account of my experience meeting film pioneer Douglas Trumbull in early 2015. This story and interview has been posted with his permission. This is part two of a three part series.

Presented here is the first half of a transcript of my conversation with Douglas Trumbull. You'll notice that the primary topic started as the evolution of space and space travel in films over the decades but quickly turns into two lovers of the technique of filmmaking just having a wonderful conversation about miniatures, optical effects, and so much more (especially on the second half, which will be posted tomorrow).

In your opinion, why do you think filmmakers have been so compelled by space or space travel as a setting in their films?

TRUMBULL: Well, you know, I'm not sure I could speak for other filmmakers, I can only speak from my own particular interest and proclivity, I guess about space films, is that most, if not 99.9% of all movies are what I call grounded movies, you know, they’re cop, chase, thrillers, love stories, musicals, they are all on the earth. And I’ve been fascinated with space ever since I was born and I’ve been looking at the sky and growing up on popular science covers of UFOs and technical stuff and astronomy.

And it's just been a personal fascination of mine, which is, what’s out there beyond all this ordinary stuff. And for me as a, kind of an artist, when I was starting out as an illustrator really, I was drawn to science fiction, so I was reading tons of science fiction, reading all the great science fiction writers, and so my artist portfolio was filled with alien plants and starts and spacecraft and other places. So that was, that's been my interest all my life.

What was the first space film you saw that truly amazed you that you remember?

TRUMBULL: You know, I was, to get ready for this I started looking at some of the old stuff last night. I have this huge library of old space movies. And I think one of the things I was looking at last night was, let me think of the name of it a second… Earth Vs. the Flying Saucers. Which, and I didn't time it out to figure out when it was made relative to like The Day The Earth Stood Still, they probably were very close to each other at the time, do you know?

They were all early 50s, so here's early 50s, I’m just a kid, I was born in 42, so in the early 50s I maybe 10, 11 years old or something. And I remember consciously now thinking back to when I saw Earth Vs. the Flying Saucers and I said this looks really hokey. And I didn't realize until I looked at it again last night that it was Ray Harryhausen doing the effects, who is like one of the great masters. But it was in the early days of stop motion animation and what you call dynamation. And I remember even then when I was 10, I didn't like the effects. Now why would that be? I have no idea. But it, it's been a big issue for me all my life: how do you do it so it really looks real, because I think the universe is a beautiful, beautiful stunning place. The moon is stunning, the sky is stunning. Galaxies are stunning. And so I've always wanted to make it look great. Just as an artist, whether, I didn't even start in movies until, you know, in the, in the early 60s.

Even at 10, something pulled you out of it?

TRUMBULL: Yeah, there was something about it that just didn't look right. It was a black-and-white movie, it was stop motion animation, there was a lack of depth of field and it was kind of jerky motions quite a lot, which I was always criticizing stop motion animated movies for that. It was a unique art form at the time, it’s still around actually. But being frustrated by it, and I remember when I saw Forbidden Planet, which blew me away totally in terms of that same criticism of being much higher quality.

And I looked into it and I said well how did they do this, what happened in the making of Forbidden Planet? And what about it looked good and what about it did not look good, because it did have exteriors on this planet with just a big painted backdrop on the stage. I mean it didn't have a lot of depth and it looked kind of corny. But it did have a whole team of animators from Disney came over to MGM to make Forbidden Planet with them and help them do these matte paintings and sky backgrounds and the saucer and some of the effects. And I just thought it was a big leap forward, also a leap forward in sound effects as well.

You remember the sound effects for Forbidden Planet. So I think that was a really stunning moment for me in realizing that a sci-fi movie could actually be pretty good, you know, it was based on Shakespeare. And then there was The Day The Earth Stood Still, which was great.

So when you went back to your library and looked at some of the space films and space traveler films, what were some of those that you find were the most influential?

TRUMBULL: One of the most influential films I saw, and it happened when I, in the very early 60s when I was working at Graphic Films. I was just starting my career as a space illustrator for these space films for NASA and the Air Force that predated 2001 and actually predated To The Moon And Beyond was a movie called Universe, made by the National Film Board of Canada. And we looked at that movie over and over and over. It was all animated, it was all kind of multi-plane, multi-pass photography of billions of stars and depth and planes of galaxies flying through. And it was black-and-white, it was shot in 35mm and it was really stunning, it stands out today as one of the best space films ever made.

And I didn't know until later that Kubrick had been watching that movie extensively over and over and over, studying that movie with a microscope to see how they did it. And then he hired Wally Gentleman, who worked for the National Film Board of Canada to come work on 2001 in the early phases of the movie. Wally got sick and so he didn't stay on to the production. But that's really one of the best space movies ever made, that was really one of the big moments for me when I felt there's really, there is hope for this whole thing. And we used that as a reference for To The Moon And Beyond, which just briefly predated 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Was Destination Moon one of those films?

TRUMBULL: Well I saw Destination Moon when I was very young, you know, and it was a - - my own response to it at the time was that it felt kind of hokey and corny. And it also had a big, I think it was a lunar surface that was a stage with a backdrop, painted backdrop. There were no real opticals to a great extent during the live-action stuff on the lunar surface. And the spacesuits looked kind of corny. And I remember as a kid just not being impressed. I was very scared nevertheless.

And I had a really hysterical moment when I was very, very young right about the time my mother died when I was about five years old. Having seen Destination Moon, and then I went on a hike and I was up in Oregon visiting my cousin and I went on a hike and there was this clay ground that had been broken and crushed like the surface in Destination Moon and it completely freaked me out. I went hysterical. I suddenly thought I'm on the moon and I'm going to die. So it had an effect on me, you know, so it's a mix of big effect and corny effect.

Alfonso Cuarón mentioned he founded it hokey, but he loved how they dealt with gravity. Especially how they would use wires.

TRUMBULL: Yeah, there are a lot of, you know, classic techniques of wires and rigs and shooting upside down or trying to create zero G and that was prescient, you know, trying to do that, figuring how to do it.

Prior to the 1960s before we started with Mercury and Apollo missions and Sputnik, filmmakers like Fritz Lang and Melies, how are they interpreting space with what little information they had?

TRUMBULL: Well I think that they were all making their effort that was appropriate to their moment in time with whatever reference materials they had, no one had ever been to the moon, no one had ever seen the moon up close. There were certainly good astronomical photographs of the moon taken by telescopes that were quite stunning so everybody knew they had craters and, you know, rills and all this kind of stuff that was what the moon was supposed to look like.

But I felt, and I still feel that the evolution of the processes that we had at our disposal, that any filmmaker ever had, whether Fritz Lang had or Melies had, at their period in time started with being theatrical. It was stagy, it was a painted backdrop, it was a set, it was props, it was lights on a stage with cameras. And that started to evolve over time into a much more sophisticated art form where you could project a background or superimpose a background or ultimately do a blue screen film background or any other number of stepping stones along the way that made it get better and better.

And all of us, anybody in the movie industry, whoever they were doing visual effects or producing or directing or production designing movies wanted it to be better and you were limited by the tools available to you at the time. So there was this incremental sweep that goes over time.

Wasn't Melies a stage illusionist?

TRUMBULL: Yes. Well, I think it's an interesting idea that movies came from stage illusion. You know, the time of Melies doing tricks on stage, trying to fool an audience, doing kind of a optical magic show, so to speak, of having props and sets and lights and illusions and stuff on stage to a live audience, then become, became projected images with slides and then silhouettes and silhouette performances. And then lighting effects and then projected images and then the projected images became motion picture images and then that became silent moving, movies. And so there's this thread that goes all the way through and starts back with stage illusion, pre-movies.

Trip to the Moon was a fantasy, and then you start to see films become more realistic as we start to see images of real life lunar landings on TV. How did the technique then have to change… using different types of visual effects and techniques to make it more realistic?

TRUMBULL: Well again, I look back on one of the big touchstones for me which was Universe. And they built beautiful, beautiful miniatures, what we call forced perspective miniatures so there would be a big boulder in the foreground and then it would gradually go back to smaller and smaller and smaller to the infinite edge of the limb of the moon or whatever, or a planet or whatever they did in this movie of increasing the perspective by graduating the texture and the lighting and everything. So it looked deep even though it was only 4 feet or something for depth of field.

And it was really an impressive scientifically based attempt to try to replicate what anyone would've thought it would be like to be on the surface of Mercury at super high temperatures or be on a comet where it’s venting gases, or to be on the moon were it's completely sharp-edged rocks and things. And… stars, you know, were a classic problem throughout movie history, which is how big are they, how real are they, how do you make stars?

We went through a huge star thing on 2001, I'll tell you. And ended up painting them, those are all just spattered white paint on black paper. About that big, all the stars in 2001 are about that big. And did it with an airbrush, so I made all the stars in 2001, but it's not that we didn't spend months drilling holes in sheets of aluminum and finding out that human beings, if they are given a drill, make it too regular. It just didn't look real, it didn't look random, it didn't look natural. It just was, Kubrick wanted the stars to be pin sharp and in focus and realistic.

And we had to face this real problem of shooting the film in 70mm but knowing that 35mm print down, so it would be actually more of those than the 70mm prints. And the stars would disappear, they would be there in 70mm, but in the 35 print they would be gone. But then in the Technicolor prints that we made for 2001 in those final days of Technicolor, they would be there because it was a different printing process.

So it's a compromise, because ultimately it's going to end up on television and you say well the stars are just gone. They are just not there at all. It's almost like you want to make different versions of your movie for all these different mediums. There's just no perfect way to do it.

And there were rear projected start fields on the windows and things on the craft you had to deal with as well?

TRUMBULL: Yeah, one of the big problems that I've seen, you are probably going to have others talking about stars. We found out, Richard Yuricich and I were partners for years in Blade Runner and we worked on 2001 and Close Encounters. Close Encounters was a really good example because we had night shots of stars in the sky on a set. And because of depth of field, which is just how much focus the camera has, the distant sky would be out of focus. And we found out that it just looks terrible, out of focus stars just looked terrible and you can’t do that. So we would have shots that had falling off depth of field, you know, Melinda Dillon or somebody would be in the foreground and the background would be out of focus. But we would put the stars in at the end of the shot as a final element and make them sharp.

No one ever complained and it looked completely natural, but it was a real thing to have sharp stars with a blurred background. But that's just the way it has to be. With this film we've been doing here, we've been going through another version of star issues because of 3-D and because of this extremely wide field of view and extreme brightness and frame rate, we've got a new start paradigm that we are working with. So the stars actually appear to be at infinity and are very sharp.

And we found out that in a stereoscopic 3-D live-action scene we actually could let them get slightly out of focus and it looked completely natural because it was, everything else in the shot was going slightly out of focus as well and it actually works okay. So it's a moving target, there is no, there's no one answer.

You have to figure out of depth of field with that Z axis being completely in focus?

TRUMBULL: Yeah, because a stereoscopic thing of being able to force the star’s apparent position to be way at infinity and it's out of focus but you're actually, your attention is focused on the actor in the foreground, as long as your attention it stays with that actor, it seems okay. If you let people start drifting around and get bored with what that actor is doing and start looking at the background, then you might have a little bit more of a problem. But I think it works out pretty well.

Space as a location, a lot of filmmakers have used it as a way to talk about different issues or Destination Moon was ultimately about the Cold War or deforestation and industry. Why do you think that is, why do we transpose these things onto space?

TRUMBULL: I mean we are human beings, you know, we have our own issues. We have our own emotions, we have our own attitudes about life and death and survival and all kinds of things. And so when you make a space movie, you are, you are automatically into an issue about survival because it's a hostile environment. And my idea with Silent Running for instance was to not even worry about that. And to make a very human, personal, emotional story because I was just coming off 2001 which I thought was beautiful. I mean I’m very, very proud of having worked on the movie, but it was cold and unemotional and undramatic in the sense that it was very edgy and cerebral. You know, 2001 is a very cosmic movie.

And so I wanted to just make a normal movie. So to me Silent Running was really like a man alone in the Arctic tundra with three sled dogs. That, emotionally that, that was the course of the movie is his relationship with his drones. It's not about whether it's going to blow up or all the air is going to be gone or he's going to run out of food or anything like that. None of the normal sci-fi things. So that was the, that was the core of the movie for me, which is just that human emotional thing, which is true for people, no matter where they are.

I've been reading a lot of stories recently about, there's a guy who's, I can't remember the astronaut’s name was spent six months on Mir. And many near-death experiences on Mir, Mir was really not a functional spacecraft and it was just constantly blowing up or catching on fire or losing air or venting gases or threatening these astronauts for months on end. And it was really a trial. And those kind of things are very real, but they are not sustainable for a lot of screen time, I don't think.

You still have to stay with the emotional core of the characters. And Gravity is a really good example of a balancing of that. I mean, she is into a really hectic survival situation, but you are able to focus on her and, you know, okay, the air is going out, or she has got to put out this fire or she is weightless or whatever. But ultimately you have to break the rules of reality and stick with the story, which I think Alfonso did really well.

There’s something about that one human being in a suit in this vacuum, void. Everything is a hostile environment.

TRUMBULL: And, and space suits and helmets are a real big problem in space movies. And, like Jim Cameron did his own take in Avatar where instead of having these big bubbly space helmets with the big ring around your neck, he just had this little plant on thing that you could snap on and off like a gas mask, much more simple and much less intrusive so that you can see the actor's face. You don't have to build a space helmet with lights inside of it so you can see the expression on the actor's face, which I just find really annoying.

And I'm sure the actors find it annoying. And I can’t imagine the world of being an actor or actress in a space helmet most of the time, because it's just got to be horrible to try to perform. So you want to find ways to get that helmet off as, as Alfonso did very well in that movie. So let's see what she is feeling and not have to look through glass too much.

Once we do plant our feet on the moon, filmmaking changes and a few people pointed out that the original Star Trek series was on the air at the point where we actually landed on the moon, and it didn't do that well because people were more interested in what they were seeing on TV. They were actually seeing Neil Armstrong and seeing these real people and being in that sort of environment with them. How did filmmaking shift from that point forward, especially leading into 2001?

TRUMBULL: 2001 was right at the cusp of that, you know, it came out of 1968 when we landed on the moon in 1969, I believe. And we didn't know exactly what it was going to look like, I had huge arguments with Stanley about what I thought the lunar terrain would look like. And I was correct but he got his way. He wanted it to look like craggy mountains and all that stuff. But it didn't hurt, it didn't hurt the film but I think the film would have been better if we had had these soft kind of rills and powdery looking rocky crater surface.

But I think the thing that happened as a result of the actual being on the moon is that it became like live television, it became almost like sports or something where you've got what looks like surveillance cameras, you know, because they were very careful to, you know, before Neil Armstrong puts his foot down, someone has got a camera photographing it. And I always think about well, who is the camera? How did the camera get there before he set foot, you know, that kind of logistics.

And so there was this kind of raw, edgy, almost impossible to even decipher kind of imagery that was low resolution, flickery, noisy, blipping in and out and everything that created a kind of hyper realism that's almost like a crude electronic documentary that then started pervading space films and science-fiction films of trying to get more gritty, trying to be more handheld.

And being handheld is really hard when you're doing a composite shot because you've got to match the movements and all this kind of stuff. So one of the big issues that we faced in the simultaneous production of Star Wars, which my father worked on with John Dykstra and Close Encounters which I was working on with Steven Spielberg was motion control and how to actually allow camera movement during a composite shot.

That was the big thing we had to solve. And so we had two teams building electronic, you know, computer controlled step remote controlled camera movers for Star Wars and Close Encounters simultaneously. And we had this kind of competition going on that was a lot of fun. And it was very good-natured, but it was trying to free up the camera to be more natural. So that, you know, we had shots, I think we were the first people to shoot motion controlled camera tracking on location in Mobile, Alabama where, you know, François Truffaut was here, and the camera’s looking at him and he is going to walk and do a 180° pan and reveal three UFOs out at the end of the landing pad.

And you had to track that and capture the motion that the camera operator did. And that was a real first. It's not like that wasn't tried before. There was a wonderful motion control system, I think it was designed by Claire Schleifer at MGM, much previous to that. Which was used on many films at MGM where they actually recorded camera motion on vinyl records and played them into a camera with motors by some means. And then there was this motion control system that Wally Veevers built for 2001, which we used which was very successful in allowing a certain amount of camera freedom, but you'll see in 2001 for instance all the movements are constant speed.

It never slows down, never goes back, never changes rate or anything. It was constant speed. And that technical limitation of just having a whole bunch of motors connected together electronically, they're all running at the same speed with different gearboxes, but that gave the movie this kind of balletic constant motion, almost like a dance, which in retrospect made the Blue Danube Waltz work. And Kubrick certainly didn't anticipate that and he wouldn’t find out until he cut the movie, and then started looking for a musical score and then suddenly you see oh, now these two things fit together, this kind of music and this kind of motion fit together.

Now we can do anything. Now you look at movies today, particularly Gravity and it's moving all over the place without cuts. And it's amazing, but it’s a completely new world that's been opened up by computer graphics.

Using those automotive robots as their motion controlled cameras and they are spinning around 360°...

TRUMBULL: Yeah, I think that was, you know, that was a component of it. I find automotive robots to be really scary because they're extremely, they could just whack your head off if something goes wrong, if there is a loose wire, that thing is just gonna go ballistic and runaway motion control systems are secret stories of the movie industry where a camera will just head down the track and, you know, go off a cliff. So those robotic things that Alfonso used in Gravity, to me were scary.

But extremely effective because it's really mostly an animated movie with those camera moves added to put the actors into the helmets. That's an oversimplification. But it's that kind of freedom that has now been allowed by this extremely sophisticated electronics and extremely sophisticated technologies we have, like Avatar. That's a completely deconstructed movie process. It's not even directed conventionally. You never, you know, he's not aiming his camera at actors. He's just motion capturing performances and then piecing it together and then putting together his, he’s post directing a movie. It's the weirdest thing.

It's complete deconstruction of classic cinematography or editorial style or cinematic language. And that's freeing. And I think that's one of the big touchstones that I see in movie history and space movies and Avatar is a good example, is that it's the geekiest movie of all time, it's completely technologically out there, it was extremely expensive and yet he's a great director and it's the biggest grossing movie of all time. That's got to tell you that the audience wants something new, they want to be there, they want to feel that they are in the movie, they want to be immersed by the movie, they want to be flying, they want to be jumping off cliffs, they want to be on whatever, like a theme park ride.

And so I really take that to heart now, and that's where I'm trying to head with the work that I'm doing now is to try to who allow the audience to feel like they are actually there. And that's an important set of components to put together.

I would imagine for you as a filmmaker, inventing things and constantly improving things has got to make it more fun and interesting, but it translates to the audience as well?

TRUMBULL: I could talk about this forever, but the movie business that we all know so well that we think we love and we know has been 24 frames a second ever since the Jazz Singer in, I think 1927 and we haven't really criticized or critiqued that. And that, that speed was limited by celluloid film, sprocket plastic and mechanical claws that were moving the film from one frame to the next and closing the shutter between. And we’ve stuck with that, but now that we've made this amazing transition from celluloid to digital, I think it's time to just reevaluate the whole thing because we don't need to carry forward all those old limitations because they are not limitations anymore.

You don't need a shutter anymore, you can go any frame rate you want. You can change the screen size, you can change the brightness, you can change all the qualities of the movie. And my personal interest as it relates to space movies is to make you feel like you are in space. That is what I think people want to experience safely. They want to be in their seat, they actually don't want to go into space. You know, and so Richard Branson is trying to say, okay you can really go to space, you have $200,000, you can go into space, you can do it.

So adventure spaceflight is right around the corner and it's going to be a real thing. But for every one person who may have a quarter million dollars to go into space, there's millions of us others who just as well be safe and stay on the ground, but have that experience. So I think we are getting very close to being able to do that.

When you were talking about the rig that Wally Veevers designed, was that the 'Sausage Factory?'

TRUMBULL: It was actually. It was called the Sausage Factory and the idea, the reason, that was named because, we had to make 10 shots a day, we're just going to crank out shots like crazy, it's a factory, we’re going to manufacture shots, it's going to be easy, fast and simple. That was why it was named. That was not true. It took forever. But it was this very clever device that Wally built, which was one big motor driving everything.

And so this big motor had a shaft coming out of it and it's running at constant speed. It would go into a gearbox and that gearbox would go through a shaft to like a dozen gearboxes through shafts to these celson motors that would be these repeater motors, so whatever one motor did another motor somewhere else would do exactly the same thing. So you could link this to the focus on the camera or the tilt on the camera or the pan on the camera or the movement on a track or any, or anything you wanted to move could all be mechanically linked together electrically.

And once you turn this thing on, everything would kind of move together and then it would all move back. And then it would move again. And so you could do multiple passes and exactly match the movements. So we could do shots where there's a spacecraft and there's the sky, there's background, there’s stars, there's the moon, there's whatever and all the movements would match. Even though it was constant speed, it matched the movements. And it was completely what I would call electromechanical.

That was the limitation of the time, we didn't have computers. So when I, when I came back off of 2001, knowing that was one of our biggest limitations, I started experimenting myself with well, how are we going to do this differently? I started studying computer technology and robotics and I discovered these things called stepper motors where you could record a series of square wave pulses, even on a home tape recorder and play them into one of these motors and it would repeat that just like playing a record.

So our first motion control system was a four track stereo quad tape recorder with four different signals in it running to four different motors and they could all change speeds. They could slow up, speed down, change direction, started doing television commercials and things using stepper motors for the first time. So this was the beginning of digital motion control.

At that point were you doing multiple exposures in camera or were you already optical printing?

TRUMBULL: It was a combination of both, there would be some multiple exposures in camera and some where you would shoot separate elements and then print them together in an optical printer with various mattes and masks. So, for instance if you were shooting Star Wars or Close Encounters or a UFO or whatever, you could shoot a move where the UFO could fly through the shot and change direction and slow down or whatever or hover, you know, whatever you wanted it to do. And then you could shoot it again exactly the same but just making the object a silhouette against a white background, like we would just light up the background white and it would be a black silhouette against white, that would create a matte, and we would shoot exactly the same move again, create the matte.

That gets processed as a separate piece of film so that when you get into the optical printer, you could take that image of the UFO and the image of the background and put them together with the exact same motion and it would all fit. Not perfectly, but as close as we could do at the time. We were always struggling against what we call matte lines and black edges, which you will see in Close Encounters and Star Wars. And when George Lucas redid Star Wars, he went through and got rid of all that old stuff.

Just electronically processed it out and rotoed it out and digital compositing today is seamless. It's really perfect. So the threat is that the digital technologies we have now, and particularly digital photography and digital projection have enabled us to really rethink the entire thing. So you're seeing movies that are amazing visual effects that would've been virtually impossible 15 years ago.

It might be sensory overload because now you can do anything and everything and maybe there's too much going on.

TRUMBULL: Well, as a film maker you've got to, you've got to have a brain, you’ve got to say what is the story I'm trying to tell and how is the audience going to relate to this because all the special effects in the world aren’t going to save a movie. You better have a good story and a good performance and, you know, there's got to be something going on that you can connect to as a human being.

So all of the techniques you learned on 2001, how did you then take that and apply it to your team with Silent Running the shots of the Valley Forge?

TRUMBULL: One of the biggest things that I adapted from 2001 was front projection technology. This was a weird thing to try to explain, but it's basically a surface in the background, it's a big screen that at the back of the stage that is what is called a retroreflective screen. It's a material made by 3M and it's like billions of little beads of glass. And any ray of light that enters a bead of glass bounces right back to where it came from. And that's why reflectors on cars or retro, reflective signs, you know, stop signs, they light up in your headlights because they are what's called retroreflective.

This had been invented before 2001, but not used as extensively as it was in 2001 and basically what you do is you say well I'm going to project an image on this wall behind the stage, which is going to have this material on it, this retro reflective stuff. And you put a, your camera’s looking at the scene and in front of the camera you put a 45° 50/50 mirror okay, so you're looking through the mirror. The camera doesn't see it, just it's invisible. But from the side you project the image from exactly the same angle so the image you are projecting and the view you are looking at hits this mirror and bounces out.

The image seems to be, as though it’s coming from the camera. So it goes out, hits the screen and bounces back. And because of the brightness of this retroreflective bead, it's 200 times brighter than where it hits a person or a set or a prop or whatever. So the image stays back there. You know, the camera doesn't register that is actually shining on the bodies of the actors because it's so dim. But they exactly fill their own shadows.

So what it gets you as a filmmaker is a composite shot in real time in the camera done and you're finished, you don't have to do any optical printing or anything. And you can pan and tilt and zoom the camera. So this is what Kubrick had, this front projection machine built that weighed about 2000 pounds. It was a monstrous big steel thing with a giant 8 x 10 still photography projector, so the 8 x 10 plates that were shot in Africa could be projected onto this giant screen on the stage.

And the camera is looking through the mirror, and the whole gizmo was so heavy and impossible to move around that they decided to move the set instead. So the entire set for the treadmill sequence was on a turntable on the stage so that you didn't change an angle by moving the camera, you changed an angle by moving the set. I mean mind bogglingly complicated thing to do.

But the front projection on 2001 really looked great and didn't require any optical compositing. And I thought well, that's really, if we can miniaturize this and make it cheap and simple, I found a really wonderful engineer in LA and we built a little front projection machine that was this big with a 35mm Aeroflex camera on it and a beam splitter mirror and instead of projecting 8 x 10s, I projected 4 x 5s, which were, you know, that big. And so I shot all my plates of the backgrounds in Silent Running of stars and Saturn and the interior of dome, the dome struts and everything as miniatures.

Had all these standing by in boxes of hundreds of different angles on these miniatures and I could project them onto the set on a 40 foot wide front projection screen. And instead of having to move the set around, we could move the screen around. We had the screen was on wheels so I could shoot anywhere in that set, which was an old airplane hangar in the Van Nuys airport, and if I moved over here I just moved the screen over there. And project some, whatever background was for that shot. And we could shoot 15 of these setups a day, in addition to our normal coverage. It was mind bogglingly fast and lightweight and efficient.

And so it allowed me to bring a really higher production value to Silent Running, which was a small, almost independent 35mm movie and bring it into a budgetable thing. I mean, Silent Running was $1,300,000 at the time, very low-budget movie and bring this kind of production quality that had been on 2001. So that was just the one example of what I could bring to. And then we also, that was the beginning of motion control and I was working with John Dykstra and was shooting all the miniatures for Silent Running. And we were shooting miniatures with front projection as well.

So whenever you see a shot of the Valley Forge spacecraft, it's actually front projection so the stars behind it are being projected with this projector as well. There's a whole documentary film about the making of it. And so we were able to make this movie for very little money by just being clever. But I think one of the main themes about that for me is that in order to enable the making of your movie at low-cost or whatever, you have to build a gizmo. You can't rent it down the street, it doesn't exist, no one's ever built one before. You've got to really be nervy and say okay, I'm going to hire a guy, I’m going to build this thing and we’re going to use it and it's going to work and you’ve got to be pretty sure it's going to work because you're putting a lot at risk.

And it's that kind of balancing of risk and reward that I've been doing all my life because I'm very comfortable with engineering. My father was an engineer, I grew up around band saws and drill presses and welders. And so I became kind of fearless about building gizmos. Most filmmakers are not that way. And so I've always felt that every movie presents a challenge, and to bring something to the screen that the audience has never seen before, you have to build a device or solve a problem or make a new lens or swap a camera or do some engineering thing to enable your vision. And then when you make your vision and you make your movie, all that becomes invisible to the audience. They don’t care that you built a widget, they saw a movie they never saw before.

In my interview with him for this same project, John Dykstra mentioned when they were first in the hangar at Kerner Optical, they said they mapped out some stuff on the ground with duct tape and they started building. And they built everything from scratch. It sounds like so much fun.

TRUMBULL: It is, it is. You know, some of the happiest guys I’ve ever met in the movie industry are the people that build the miniatures because they are like in Santa’s Workshop. They just love building miniatures and they're always happy and they work around the clock, whatever you need, they just love miniatures. So that's one of the nicest aspects of movies is miniatures and I still love them and I still use them.

What are some of the challenges that miniatures present, but what are some of the advantages they give you?

TRUMBULL: The advantages that miniatures give you, if you photograph them properly, if you light them properly, you can make a miniature look fake, if you don't light it properly or you don't have the right depth of field. And I've met seasoned cinematographers that are heads of the ACE who doesn't know what depth of field is. I mean it's actually happened. And I say well it’s all got to be in focus because if it's a miniature and if anything is out of focus, it will look like a miniature instantaneously, any audience member, trained or not will say it looks fake.

So you've got to get depth of field right, and you’ve got to get lighting right you've got to get perspective right, you've got to match the focal length of the lens so the focal length of the lens that you’re shooting with for the live-action has got to match the focal length that you are shooting for the miniature, otherwise they won't fit together in space. So there's a lot of things to the art of miniatures. But my, the result is that they age very gracefully. If you look at the miniatures in 2001, it’s a really good example, the space station or any of the miniatures in that movie, they still look pretty good. They still look convincingly amazingly powerful.

Whereas if you do it with computer graphics, it ages ungracefully because the computer graphics industry is improving on the lighting and the texture mapping and the geometry every year or every month and getting better and better and better. So if you look five years back, movies made with computer graphics can suddenly look very dated. They may not, they might not hold, hold up as well as a miniature would hold up. So I think there's also another thing about miniatures, which is, excuse me, about computer graphics is that, you know, you're talking about thousands of polygons in a computer with lighting and texture mapping and all these arts that are part of trying to make something synthetic look not synthetic.

And the last 2% is the most expensive part of the equation. And often the studio or the production company will just run out of money or they just won't be able to render it the last time to get to what we call photorealism. And it might look a little bit fake. It might look a little bit corny and they're just hoping that they can cut the movie so fast that you won't notice. And I see it all the time. If you actually, you know, play a DVD or a Blu-ray of a movie they you really admire and just keep stopping it, freeze frame on that shot that you like and then scrutinize what's going on, you say oh there's all kinds of mistakes in that shot.

But it was the fact that it was fast cut, got away with it. So young people today who are playing video games are very sensitive to computer graphics and they don't like anything that looks fake. And so if you are doing too much of it or you are not doing it well, the audience can just immediately turn off and say that's just, it doesn't cut the mustard for me, I don't believe this. So I like, I like a mixture that's really mostly miniatures and some computer graphics.

I certainly love digital compositing because it's way better than any optical printing. So it's just try to find a sweet spot, and I gravitate towards what I call organic effects, which is things in tanks, natural things, miniatures, stuff that surprises me all the time with natural phenomena. Like I use a lot of dyes in tanks and things where weird stuff happens that you would never expect that no one could ever write code for in a computer to create some cloud effect. I often see cloud effects in movies that just do not look convincing to me at all because it's particle effects are like one of the hardest things to get because it's a fluid dynamics issue and a lighting issue. And I think miniatures and organic effects can be much less expensive and a lot more fun and more convincing than computer graphics.

The launch sequence in Apollo 13 comes to mind. Here’s this miniature, but they are enhancing it and supplementing it with computer effects.

TRUMBULL: Yeah, high-speed photography is another thing that actually enables some amazing phenomena that you never would've seen before. Because in the days of film, sprocketed film, you just can't move the film fast enough to shoot really high-speed. The highest speed we ever shot on 2001 was about 72 frames a second. Now with Phantom cameras or other purveyors of digital high-speed cameras you can go 1000 frames a second easily, 1500 frames a second and you will suddenly see stuff that you never would have even, would've gone by in the blink of an eye and it's really fascinating. So I'm, I'm all for that. We do it quite often around here.

I recently just saw a VFX Supervisor shoot shoot an actress with a wind machine with the Phantom camera made her hair look almost super-human.

TRUMBULL: It's very satisfying, there's just something about it. You know it's real but it's beautiful.

Next: Part Three - The conclusion of the interview, and a quick lunch before our goodbyes.